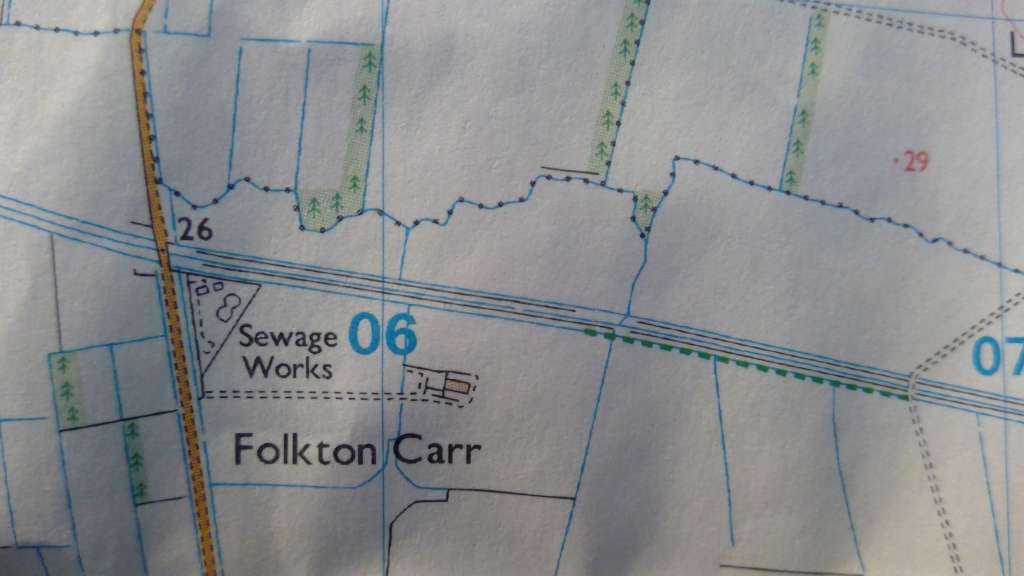

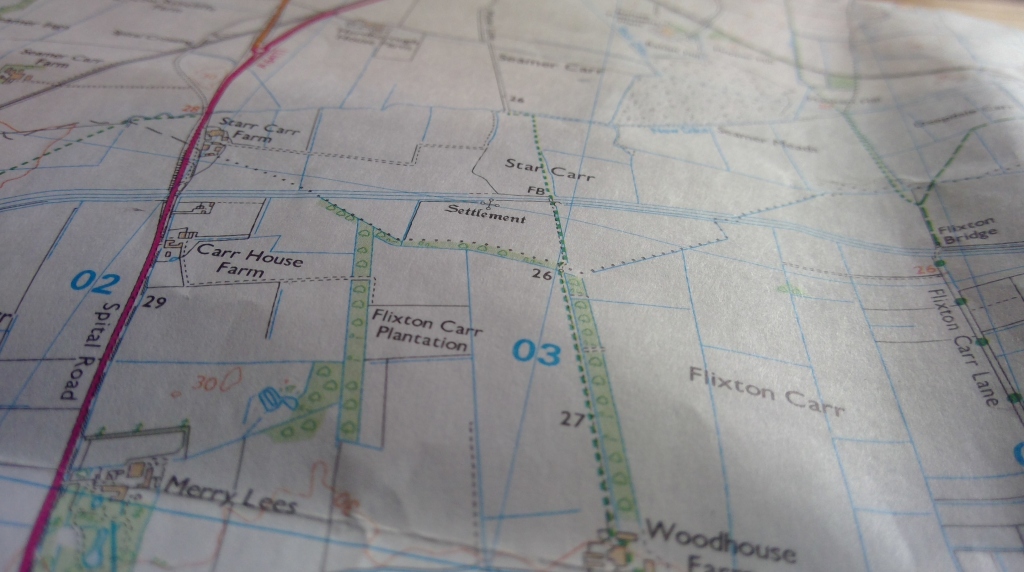

The Lake Flixton peats are nowadays largely hidden under pasture.

At the site of Star Carr today there is little to see but a patchwork of arable and pasture fields, dissected with farm drainage ditches (See more on the fascinating drainage story here). The archaeological interest lies beneath the surface. There are however some excellent museum displays of Star Carr and Lake Flixton material, which interpret and conjure-up the Mesolithic environment beautifully. There are several to choose from – all with a different slant on the story, but they are all well worth visiting.

Rotunda Museum, Scarborough

The Rotunda Museum, Scarborough http://www.scarboroughmuseumstrust.com/rotunda-museum/

The Scarborough Museum Trust’s famous Rotunda Museum in Scarborough is a small but beautiful building and currently houses an excellent exhibition of Star Carr material. The building was originally conceived as a geological museum – if you are able to visit when they do special access to see the upper gallery in the central tower – such as they have done in recent years for Heritage Open Days – you can appreciate the stratigraphic arrangement of cabinets for geological specimens. An entry fee applies – look out for free access on Heritage Open Days in September.

The Yorkshire Museum.

The Yorkshire Museum, York. www.yorkshiremuseum.org.uk – The York Museums Trust runs two museums and an art gallery in York. This one, located the beautifully-kept museum gardens (itself a great public green space close to York City centre) houses a very nicely done display of Star Carr and Lake Flixton material. There is firstly a display themed ‘After the Ice: Yorkshire’s Prehistoric People’ in which Star Carr material figures prominently. They also have what they call a spotlight display, ‘Ritual or Disguise: The Star Carr Headdresses’ which features some remarkable new frontlets to go on display and also the much publicized and unique Star Carr shale pendant, a small but tremendously important find from recent excavations. Entrance fees apply. YMT do a very worthwhile annual pass, the YMT card, for unlimited access to their three sites. The York Castle Museum is also excellent and substantially larger.

Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge. In 2018 a brand new exhibition about Star Carr opened at the Museum of Arch. and Anth. in Cambridge, called ‘A Survival Story – Prehistoric Life at Star Carr’ It is bang up to date with the latest academic thinking about the significance of Star Carr to modern humans – explaining how the Mesolithic climate and landscape was in rapid flux during the site’s occupation and demonstrates a hitherto unrecognized level of resilience and adaptability among the Mesolithic people of Yorkshire. A Survival Story – Prehistoric Life at Star Carr is on display at the Li Ka Shing Gallery at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Downing Street, Cambridge, from June 2018 to December 2019. Entry is free. Read more on the exhibition on this archaeology news network blog.

Other places to learn more

The Scarborough Borough Council-led Carrs Wetland Project has come to a close but the landscapes and heritage of The Carrs remain a fascinating subject. The pages of the Carrs Wetland Project website remain a good introduction to the amazing and under-appreciated archaeology of Star Carr and Lake Flixton. The most recent extensive excavations at Star Carr, although finished are still yielding new insights for science as the material collected is analysed and interpreted. There are new academic papers published by the Star Carr research team regularly and reported on their Facebook Page and website.

It is also worth mentioning a few groups or organisations who may run events or talks from time to time on the heritage of The Carrs. Below are some links which may prove useful, beginning with the ones more directly pertinent to the archaeology.

www.starcarr.com – The official site of the archaeology project based at University of York. Full of info from Professor Nicky Milner and her team, the people who know the site best! Keep a look out for talks or media releases by the team about their latest research. If you ever get chance to hear Prof. Milner speak on Star Carr be sure to do so. They have an occassional newsletter which is certainly worth subscribing to.

www.sahs.org.uk – Website of the Scarborough Archaeological and Historical Society. They have a regular programme of indoor talks and summer field excursions as well as engaging in research investigations of their own.

www.yas.org.uk – Yorkshire Archaeological and Historical Society.

www.cba-yorkshire.org.uk – Council for British Archaeology – Yorkshire Branch.

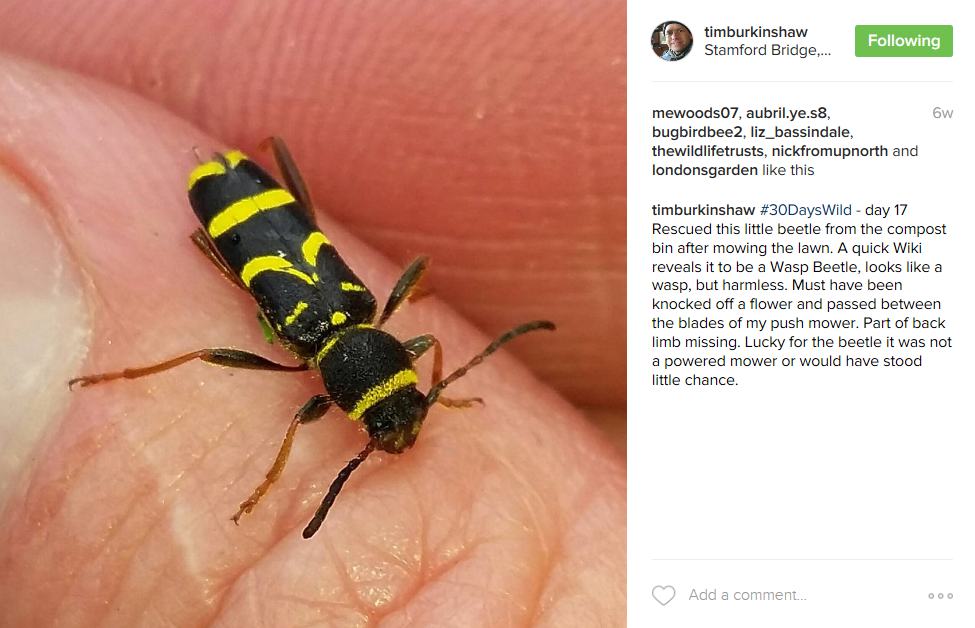

www.scarboroughfieldnats.co.uk – Scarborough Field Naturalists Society.

www.connectingfornature.wordpress.com – The website and blog for the local biodiversity partnership in whose patch The Carrs falls.